We are pleased to present more than seventy years of work by American artist Susan Weil (b. 1930, New York). This retrospective pays tribute to one of the most inventive artists of the 20th century.

Weil, whose work is in the collections of New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art and Museum of Modern Art and London’s Victoria & Albert Museum, is among the key female figures who pushed the boundaries of Abstract Expressionism, a movement largely defined by male painters. Like many women of her generation, Weil’s work and career were overshadowed by the men around her, many of them boldface names in the canon of art history. But as the narrative of modern and contemporary art is slowly being rewritten to include more women, it is well past time to shine a brighter light on the art-historical significance of Weil’s prodigious and wildly creative oeuvre.

“Susan Weil was the first artist I signed when I opened my gallery in New York in 2000,” says Sundaram Tagore. “She was the first of a number of unsung women from the New York school I’ve represented over the past twenty-three years. Great work is great work. I started the gallery to challenge the notion that Western men make the most collectible art. That hasn’t changed. It is my privilege to bring her work to ever wider audiences.”

SUSAN WEIL AND THE NEW YORK SCHOOL

In 1948 and 1949 Weil studied under Josef Albers at Black Mountain College in North Carolina, the rural mecca for young artists, composers and choreographers. She often scoured campus rubbish dumps with Robert Rauschenberg where they found unexpected materials to incorporate in their experimental works. “It was very revolutionary. Black Mountain put together creative people from all the fields,” recalls Weil, who studied painting but also explored dance and poetry. “We’d sit around in the big dining hall and talk about different things we were working on. It was great sharing. We participated in all different mediums.”

Weil moved to New York in 1949 with Rauschenberg, to whom she was briefly married, when the art scene was erupting. She came of age at the center of the New York School, with its eclectic cultural influences and interdisciplinary collaboration. Her peers included Elaine and Willem de Kooning and Jasper Johns as well as Merce Cunningham and John Cage.

While the New York School consisted largely of American artists, their impact was international in scope. Weil was a key figure among this group of artist-pioneers whose experimentation with unusual materials and techniques would later influence artists across the globe. When she introduced Rauschenberg to the blueprint technique, which she used to create life-size cyanotypes of human figures and foliage, it had an indelible impact on his practice. He later went on to stage a significant exhibition featuring work in China in 1985, which in turn inspired Chinese artists to explore new approaches to art-making.

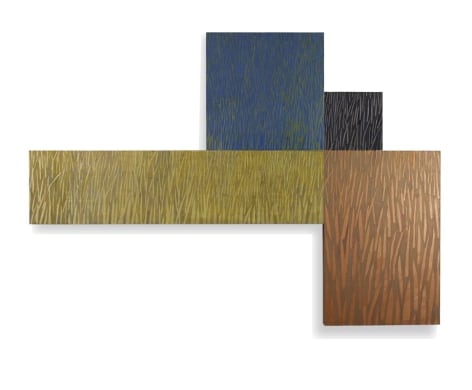

Although Weil was active in New York during the height of the Abstract Expressionist movement, she was not afraid to pursue figuration and reference reality, gaining inspiration from nature, literature, photographs and her personal history. Throughout her long career she has consistently brought to life intangible qualities of time and movement, creating multidimensional works in which she fractures the picture plane, deconstructing and reconstructing images. She also consistently experiments with quotidian materials, including found objects, metal, paper, Plexiglas, repurposed textiles, recycled canvas and wood. The dynamic and playful results are crumpled, cut and refigured compositions that invite viewers to contemplate multiple perspectives at once.

EXHIBITION HIGHLIGHTS

Tracing the arc of Weil’s seven-decade career, this exhibition includes an abstract landscape articulated in vivid shades of green from 1969. Alongside are several striking figurative works. Weil’s nebulous human forms are one of the themes she has returned to again and again and still explores today, namely, time expressed abstractly and in relation to nature and the figure in movement.

The show features several of Weil’s iconic blueprint works, part of a long-running series (1949 to the present) in which she utilizes a monoprint process she has experimented with since childhood. In 1949, Weil introduced the technique to Robert Rauschenberg and together they created a series of blueprints through 1951. The works were featured in Life magazine that same year—a notable achievement considering how a 1949 profile of Jackson Pollock in Life became a significant turning point in his career. In 1992, one of the blueprint collaborations was acquired by the Museum of Modern Art in New York for the permanent collection.

Also on view are tactile sculptural formations made from draped or crumpled canvas painted on both sides in bold color. Weil has cited the sensuous folds of fabric found in Renaissance art as inspiration for these dimensional works, a technique she has explored for decades in her Soft Folds series.

Always willing to experiment, the artist created several works especially for this exhibition using a new technique. Through trial and error, she discovered how to fracture the picture plane literally by creating controlled cracks in glass and mirror. In Quarter Past Four, a quadriptych glass grid, Weil emphasizes the fissures by filling them with white grout to accentuate the circular shape they form, while the single mirrored panel brings the viewer into the work. “I’ve spent a lifetime working. It’s been both a serious and a joyful journey and I have no intention of slowing down,” says Weil. At 93 years old, Weil is breaking glass in more ways than one.